|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|||

|

Introductory Information on Autism and Asperger Syndrome(Adapted from Beyond the Wall: Personal Experiences with Autism and Asperger Syndrome By Stephen M. Shore) IntroductionA question that I often hear when I give a presentation or work with children on the autism spectrum is "What is Asperger Syndrome?”. Is it autism? Where does Pervasive Developmental Disorder-Not Otherwise Specified fit all into all of this? Are they the same? I believe as well as many others (Attwood, 1998) that these three diagnoses are all part of the autism spectrum. Pervasive Developmental DisordersPDD-NOS, Autism, Asperger Syndrome (AS) and other disorders are currently classified under a group of disorders known as Pervasive Developmental Disorders (PDD) by the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders of the American Psychiatric Association, 4th edition-revised (DSM IV-TR). The diagnoses that fall under the PDDs in the DSM IV-TR exhibit impairments in communication, social deficits, along with restricted and repetitive interests and activities. However, these attributes differ in terms of severity for the diagnoses of autism, pervasive, Asperger Syndrome, and Pervasive Developmental Disorder - Not Otherwise Specified. The diagram below, as adapted from Bryner Siegel’s The World of the Autistic Child (Siegel, 1996, p. 10), clearly shows where the autistic disorder fits into the umbrella of the pervasive developmental diagnoses.

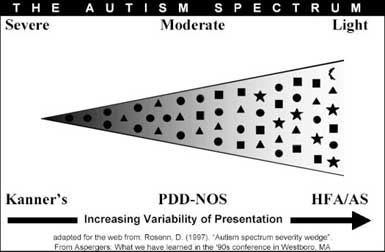

However, this depiction isolates autism from the diagnoses of Asperger Syndrome and Pervasive Development Disorder - Not Otherwise Specified and fails to describe what I feel are the true relationships between these disorders. Asperger Syndrome and Pervasive Developmental Disorder - Not Otherwise Specified (PDD-NOS) are not classified as part of the autistic continuum. Addressing autism, Asperger Syndrome and Pervasive Developmental Disorder-Not Otherwise Specified by what they have in common makes it easier to understand their relationship to each others and the Pervasive Developmental Disorder in general. These three diagnoses share the specific delays in social interaction, communication and restricted repetitive and stereotyped patterns of behavior, interests and activities. PDD-NOS is often used as a catch-all in which to cast children who exhibit a certain number and severity of autistic traits. Often the examiner doesn't quite know where to place the child or wants to protect parents and child from the stigma of an autism diagnosis. The reality is that an autism diagnosis will provide more services in many school municipalities. Thus it should be used when it is appropriate. Perhaps an even better way would be to place more emphasis on providing what a child needs as opposed to getting caught up in which “brand” of autism is involved. To this end, considering autism as a spectrum disorder with varying degrees of severity and presentation may be of help. The Autism SpectrumWhen examining the criteria of these diagnoses in the DSM IV, it makes more sense to classify autism, PDD-NOS, and Asperger Syndrome as a separate category -- the autism spectrum. Looking at these three disorders as part of the autism spectrum does more to bring them together based on their similarities rather than dividing them into distinct categories.

This diagram as developed by Daniel Rosenn, M.D. (1997) shows autism as a spectrum disorder with different levels of severity and presentation. Considering autism as a continuum of its own may help solve the problems of defining and classifying people who are within the autism spectrum. The cluster of circles at the Severe-Kanner’s end of the graphic depict the relative ease of diagnosing autism in a person when she is at this end of the spectrum. Towards the moderate area, the presentation of autism becomes more varied as indicated by the introduction of different shapes such as the square and the triangle. The high-functioning-Asperger (HFA/AS) portion of this syndrome has the greatest diversity in shapes because the variation in presentation along with the number of people with autism in this area is the greatest. At the extreme right, those with autism blend into the general population. This autism spectrum severity wedge diagram shows that it is impossible to state unequivocally that a person with autism must have a particular trait or cannot have another trait. There is a point where a person may actually move off the autism spectrum. The person still has the tendencies but may be considered an “autistic cousin.” Coined by Autism Network International, the term “autistic cousin” refers to a person whose autistic tendencies are not strong nor numerous enough to be considered as being on the autism spectrum. At this point, it can be difficult to tease out whether certain attributes result from personality or from the autism spectrum disorder. Perhaps it doesn’t matter as long as the person with these issues receives the needed accommodations and understanding. While one shouldn’t blindly pigeon-hole children into any one of these categories, it appears to me that most children with autism fall mainly into one of these categories with possible small overlaps into the others. ReferencesAmerican Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders of the American Psychiatric Association (4th. ed. Rev.). Washington, DC: Author. Attwood, A. (1998). Asperger’s Syndrome. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. Rosenn, D. (1997). “Autism spectrum severity wedge”. From Aspergers: What we have learned in the ’90s conference in Westboro, MA. Shore, S. (2001). Beyond the wall: Personal Experiences with autism and Asperger Syndrome. Shawnee Mission, Autism Asperger Publishing Company. p. 146. Siegel, B. (1996). The world of the autistic child: Understanding and treating autistic spectrum disorders. New York: Oxford Press.

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Biography of Stephen Shore | Writings | Links | FAQ | Contact Stephen Shore | Home |

|||||||||||||||||||||